07.02. - 23.05.2020

In 1740, Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin painted a small picture* of a monkey - here one of the lemur genus - who, well dressed and with a two-pointed hat on his head, sits in front of the canvas with a brush and a stick, and tried to paint the figure to the right. So the work shows the artist as a monkey, who instead of education only has the ability to reproduce. Or to put it more sincerely: he shows the artist as a monkey who can adapt and wants to be willing to criticize. It is also rumored that Chardin's image expresses his silent visual criticism of less important colleagues who received a free royal pension in the Louvre before him.

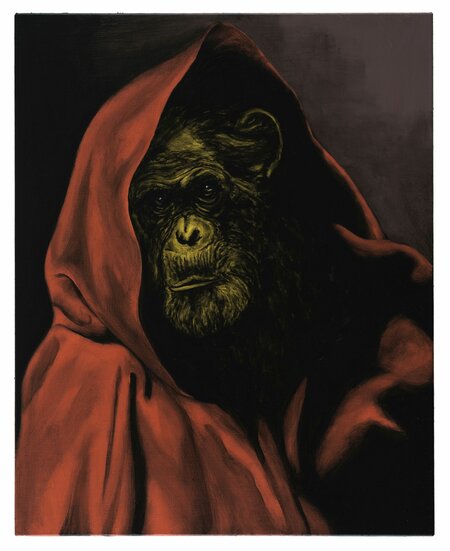

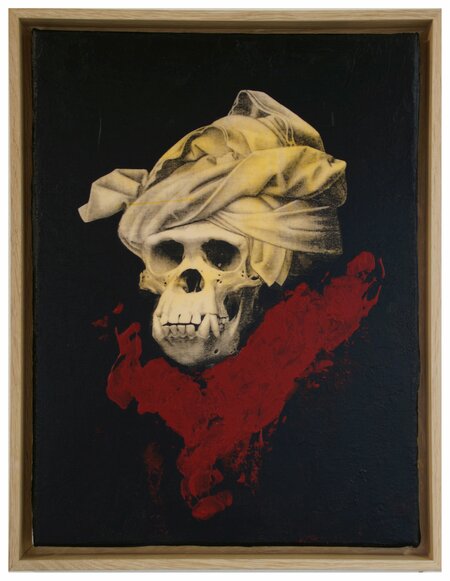

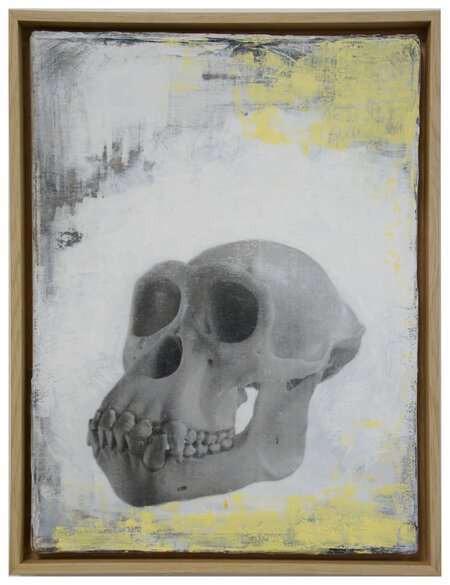

Even the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, who achieved great renown through his encyclopedic work on natural history, describes the characteristic of the monkey as an animal with human-like features and with a habit of always imitating people, as a kind of caricature of it. The bestiary of the Middle Ages, however, link the monkey with the image of the devil and evil and thereby emphasize its malicious and superficial character.

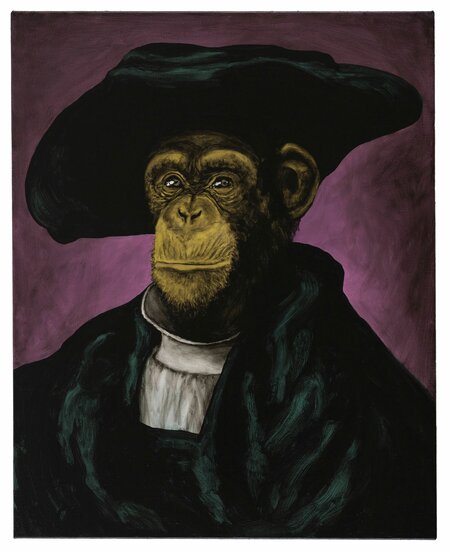

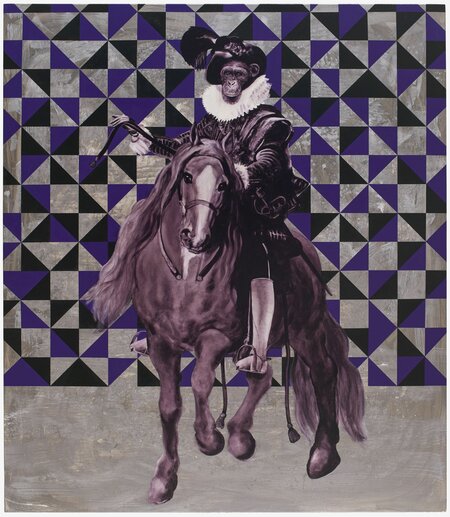

Despite all of this - or perhaps precisely for these reasons - the monkey found his image motif again and again in painting, both in the old masters and in the modern to the present day. In the so-called Les Singeries from the 17th to 19th centuries, the monkey even took on completely human roles, such as those of the inn goers and their drinking, those of the world travelers or those of the pipe-makers in a smoking salon, seen by painters like Ferdinand van Kessel (1648 - 1696), David Teniers (1610 - 1690) or Sir Edwin Landseer (1802 - 1873). But the most consistent in terms of its context remains Chardin, who shows the monkey in his penchant for mimesis as a mindless imitator, who paints well and sometimes badly, just as luck would have it.

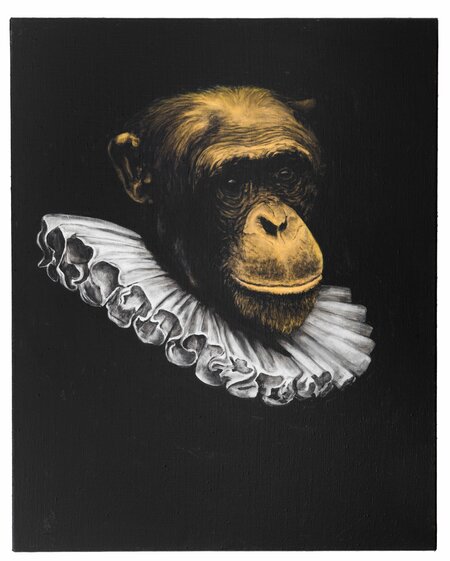

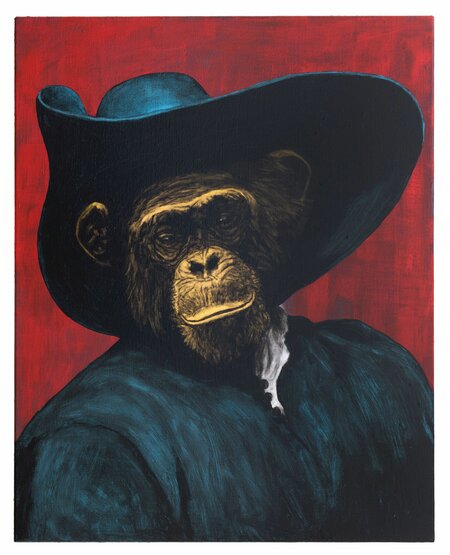

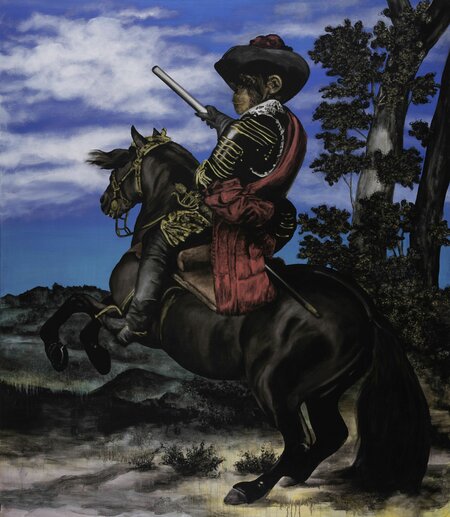

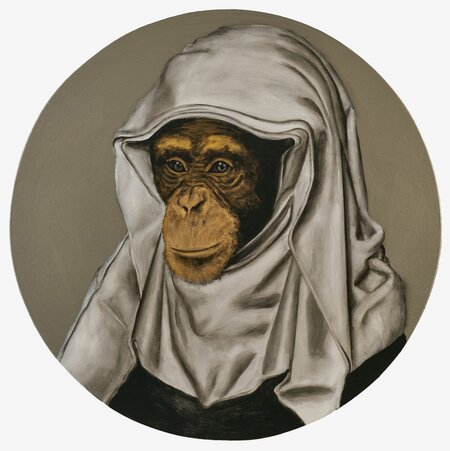

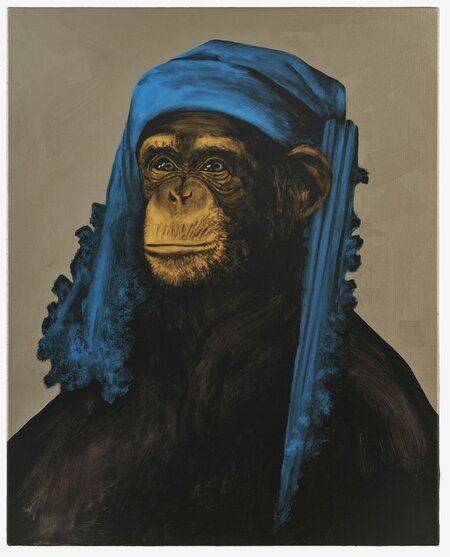

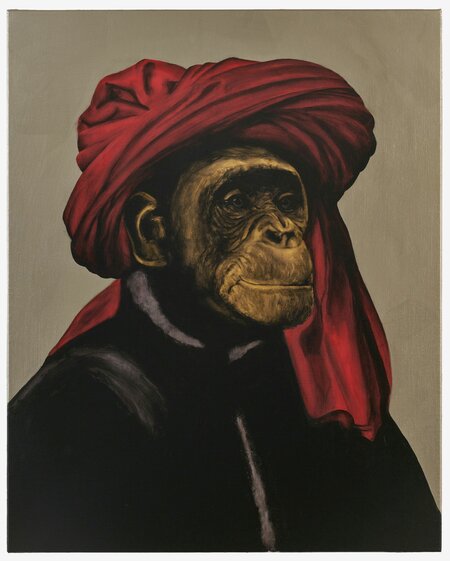

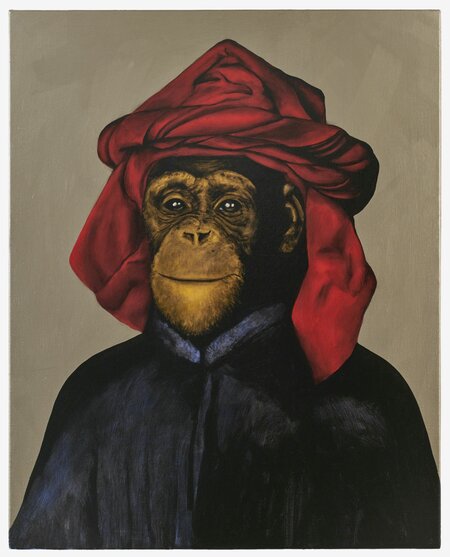

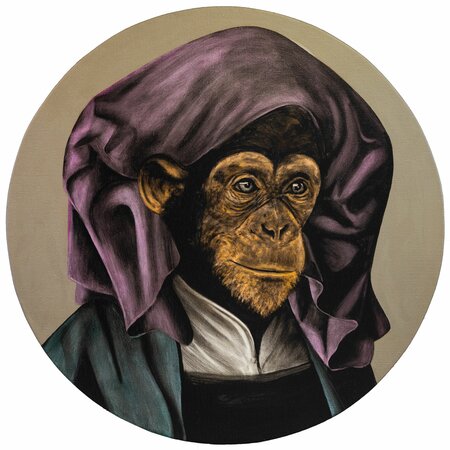

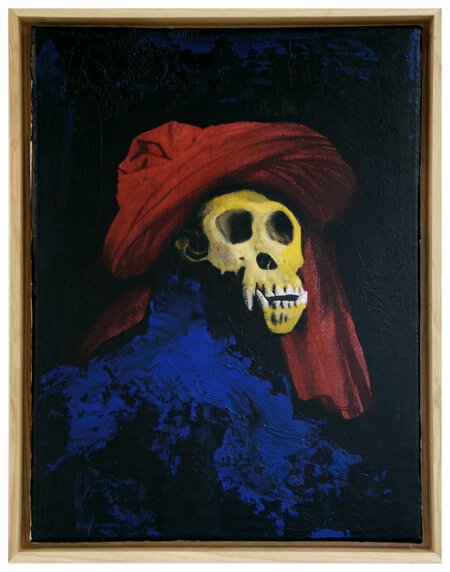

As with Stefan à Wengens ghost portraits (2005) and the original gurus (2014 - 2017), strictly speaking, and recognizable through collages, he initially creates fakes, which are then turned into originals again through their implementation in painting with their guaranteed claim to truth. In the Le Singe Peintre series, however, he usedsportrait paintings from, among others, Frans Hals, Rembrandt, van Eyck or Bruyn, in which I swap the heads and hands with those of a primate. It is a game similar to that of his fellow countryman Rémy Zaugg on a conceptually abstract level with his Le Singe Peintre series (1981), in which, as it were, he varied the idea of ??Singe Peintre rather than the image, and in it as a director, Monkey, actor and author put together in one person.

Has the artist now instructed a monkey, perhaps even one with Stendhal syndrome, to paint his own like a Van Eyck painting? Are the pictures possibly an ancestral gallery of later relatives of the lemur Chardins? Or is he, who apparently plays a game and slips into the role of a great ape in order to imitate the old masters "unconsciously" and with relish? Is it that role of the primate that is still very conscious of its subconscious? Or are his monkey portraits even a mirror, the provision of which is to be understood as a broken ironic gesture towards criticism and the art world, similar to Chardin's anger and discomfort towards certain colleagues and influencers in cultural affairs? Great primates!

Even the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, who achieved great renown through his encyclopedic work on natural history, describes the characteristic of the monkey as an animal with human-like features and with a habit of always imitating people, as a kind of caricature of it. The bestiary of the Middle Ages, however, link the monkey with the image of the devil and evil and thereby emphasize its malicious and superficial character.

Despite all of this - or perhaps precisely for these reasons - the monkey found his image motif again and again in painting, both in the old masters and in the modern to the present day. In the so-called Les Singeries from the 17th to 19th centuries, the monkey even took on completely human roles, such as those of the inn goers and their drinking, those of the world travelers or those of the pipe-makers in a smoking salon, seen by painters like Ferdinand van Kessel (1648 - 1696), David Teniers (1610 - 1690) or Sir Edwin Landseer (1802 - 1873). But the most consistent in terms of its context remains Chardin, who shows the monkey in his penchant for mimesis as a mindless imitator, who paints well and sometimes badly, just as luck would have it.

As with Stefan à Wengens ghost portraits (2005) and the original gurus (2014 - 2017), strictly speaking, and recognizable through collages, he initially creates fakes, which are then turned into originals again through their implementation in painting with their guaranteed claim to truth. In the Le Singe Peintre series, however, he usedsportrait paintings from, among others, Frans Hals, Rembrandt, van Eyck or Bruyn, in which I swap the heads and hands with those of a primate. It is a game similar to that of his fellow countryman Rémy Zaugg on a conceptually abstract level with his Le Singe Peintre series (1981), in which, as it were, he varied the idea of ??Singe Peintre rather than the image, and in it as a director, Monkey, actor and author put together in one person.

Has the artist now instructed a monkey, perhaps even one with Stendhal syndrome, to paint his own like a Van Eyck painting? Are the pictures possibly an ancestral gallery of later relatives of the lemur Chardins? Or is he, who apparently plays a game and slips into the role of a great ape in order to imitate the old masters "unconsciously" and with relish? Is it that role of the primate that is still very conscious of its subconscious? Or are his monkey portraits even a mirror, the provision of which is to be understood as a broken ironic gesture towards criticism and the art world, similar to Chardin's anger and discomfort towards certain colleagues and influencers in cultural affairs? Great primates!